You Can’t Call Yourself Smart Until You Can Define These Three Words

Don’t worry, I still Google the difference between metaphors, similes and analogies quarterly too.

In this issue

• Metaphor vs. Simile vs. Analogy (finally explained)

• Why we forget and why that’s essential

• How to learn better by teaching yourself

• A Neuro Gum giveaway for our June-refer-a-thon!

Why the weird email timing?

Each issue goes out when one of my sons were born and made me whole.

This one comes at Oscar’o’clock - enjoy!

Anyone who's ever tried to learn a thing knows that it's often much easier to forget two.

For those who fret over their forgetful nature allow me to console you: forgetting is in fact an essential part of learning. More than that, we can lean into concepts like the forgetting curve to improve our own learning outcomes, more on that in my Psychology Today post here.

Thinking positively, what all this means is that we get second chances at learning something we’ve felt worthwhile committing to memory. Third ones too.

Like today, when I yet again felt compelled to look up the difference between a metaphor, a simile, and an analogy. The exact number of attempts at learning this escapes me, and so, apparently, do the definitions I’m so keen to get one of my neurons to commit to.

And before you start questioning how I spend my days that are now well funded by investor dollars, know that I’ve long since outsourced my rote memory to Google.

Ask me when the Boston Tea Party happened and I’ll give you a ±20 year range with entirely unearned confidence. Historical trivia and I are uneasy neighbors, and when one enters the room the other usually leaves. Historical insights and the deep patterns they reveal is an entirely different story, and uncovering more of them is the driver behind the third academic prong in my life.

Across all the domains I commit to, I do my best to try and retain thought patterns, structures, key distinctions and explanatory frameworks. These are my cheat codes for thinking better on the fly.

As much as I’d want to pretend to be in it for the deep insights, I’ll admit to also being a part-time sucker for the entirely useless esoterica that serves no other use than an intellectual flourish.

If you’ve ever corrected someone’s less to fewer, you’ll know what I mean.

And here is where we arrive at metaphors, similes and analogies. That fact that I feel consistently drawn to these terms as if they themselves wielded an organizing power over the world would probably give an evolutionary biologist much to say about my XY-chromosomed condition.

The fact that I have never been able to make what I’ve learned and re-learned stick, speaks more to the act of learning, which I assume you might in the business of too.

Before I give you an idea on how to get better at making thing stick, let’s get the definitions that have vexed me for decades out of the way.

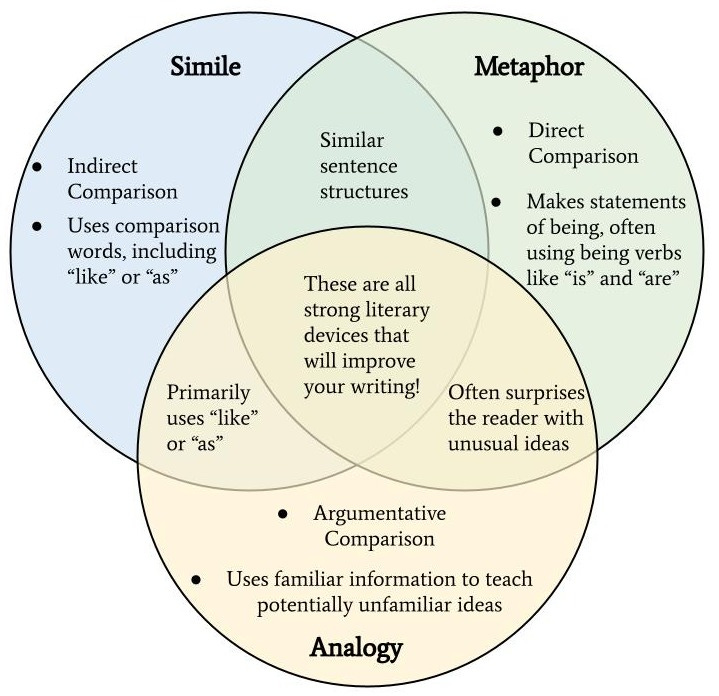

Metaphors, similes and analogies, all are tools of comparison. While they are closely related and overlapping, they are not interchangeable (hence, making learning them a classic smarty-pants move).

Metaphor: He is a lion. (Ok he’s not actually a lion, but we’re equivocating the two to create a powerful emotional evocation of courage, ferocity, etc.)

Simile: He is like a lion. (Similes make the comparison is gentler, almost watered down from metaphors with a “like” or “as,” but the story we’re telling remains the same.)

Analogy: Being brave in battle is like a lion protecting their pride, it acts despite the fear. (Analogies map out relationships, often using similes or metaphors to explain a broader structure.)

To give myself some slack, clearly one reason behind the difficulty of learning the above distinctions is that they are not meaningful enough.

Metaphors, similes and analogies overlap in ways that make it hard to map clear boundaries. You would need to use them consistently, or be an expert in linguistics, for the nuance to become intuitive. The real and perceived effort required to know the difference is exactly what makes them an effective flourish.

So, how do we make this the last time I need to learn all of this?

First, let’s meet the student where he is; a. 39 years old male, for whom jargon and esoteria clearly isn’t a strength. Maybe that’s why he left big law never to return, but we digress.

Then, let’s look at the attempts at learning themselves.

If you try one way 20 times without lasting results, perhaps it's time to acknowledge a deeper learning issue here, one that’s less about the conceptual challenges involved and more about deficiencies in self-pedagogy.

Reading the definition, mouthing it once or twice, and moving on after I have felt the first sign of surface level mastery of the act of repeating vs. ability to apply, clearly isn’t the way to go.

Let’s also be honest about how my motivations here haven’t exactly been noble.

What’s driving this particular obsession is an unvoiced desire to win an extra point in pub trivia, or to sound clever in a podcast. A sad little ghost of performative intellect that still whispers, “Wouldn’t it be nice to be the guy who actually knows this?” Yes it surely would, says a part of my brain, and on we go back to the Oxford dictionary.

For self-driven learning to work, it needs to be intrinsically motivated with something that has a half-life longer than a glass of milk.

Simply put, the stakes for learning these distinctions have never been high enough. No one's job, freedom, or dignity has ever hinged on whether I used “simile” correctly.

Even kids, our little language sponges of which we have three at home, don’t spend their time absorbing words they sense to be meaningless. Instead, they learn meaningful connections between words and (initially real life) concepts through repetition and exposure, with higher stakes leading to faster and more sustained uptake.

The other mistake I’ve made is the ‘one and done’ fallacy that omits how forgetting follows learning on a predictable curve. To beat it, you have to meet it by repeating it.

What isn’t tested or routinely encountered won’t be retained, and with the limited use trio of concepts here have in the real world the only sustained path to remembering them is testing myself on them.

And that is a bridge too far for an intellectual flourish, even for me. A

t best, I can dedicate a Google Keep note to these, but only to make finding the definitions easier when the urge to relearn them comes next.

But I suspect there might not be a next time.

What I’ve found in my more than a decade of flirtation with academic positions and teaching is that teaching a thing is by far the best way to learn a thing.

In fact, this post was all a big con, born out of nothing but an entirely selfish desire to never again have to relearn how metaphors equivocate as is, similes water down and analogies mix. Thank you for being the unsuspecting audience.

I’ll tell you how it all panned out, and the next time you see me test me on it. If I can’t answer, don’t send me back to the books. Send me back to teaching and writing!

And the same goes for you. Even if you don’t have a classroom of your own, you can still teach what you want to cherish and foster, even if it means taking your audience on a ride.

More of my tips on on learning and how to embrace the difficulty of it here, and share with a friend who might need one more thing stuck in their head.

A book to read

This slim but entirely unforgettable book is one of my favorites on memorization. It documents the life of Solomon Shereshevsky, a man with a near-perfect memory who quite literally couldn’t forget things even if he tried.

If that sounds like a blessing, just read the piece. Luria’s work sits somewhere between neurology and narrative and shows just how adaptive forgetting actually is.

A thing to do

Test yourself on what you want to retain, periodically and intentionally

Passive review is one of the most seductive traps in learning. Reading something once and nodding in vague recognition doesn’t mean you’ve learned it as I’ve (perhaps finally) learnt with my adventure with this trio of concepts.

To actually remember, you need to interrupt the forgetting process by actively pulling the information out of your brain. That’s the retrieval effect in action and you’ll be smarter for learning this one!

A thought to have

Start thinking in terms of self-didactics

Learning how to teach yourself is one of the highest forms of intellectual independence.

The best learners I’ve seen in my career aren’t the ones who get it fastest. Instad, they’re the ones who notice when they haven’t gotten something, and go back to work on it until they have. These students coach themselves through the forgetting curve and come back stronger.

Self-didactics is nothing but the ability to monitor how you learn, how you stumble, and how to fix it, and I invite you to embrace it.

A product to love

Neuro Gum

I tried Neuro Gum live on my podcast with the founders who were about to head off on a seven-day bachelor party bender in Japan (which, honestly, might deserve its own podcast).

I popped my first piece at minute 0 and recorded the effects as it started to kick. Clean, focused energy without the jitters, and now a part of my carry-on.

Thanks to the Neuro team for sponsoring this month’s giveaway. The product’s vetted, the vibes are good, and the Curiosity Code podcast with the founding duo drops this fall.

Recent writings on Forbes and beyond

Latest: The Power of "No": How Rejection Builds a Life Worth Having (Psychology Today)

Why This Nasdaq Listed CEO Changed His Mind About AI, And What It Took (Forbes)

Declining Birthrates Are Breaking The Economy. Can We Fix It In Time? (Forbes)

In Defense of Intuition: Why Gut Feelings Deserve Respect (Psychology Today)

Your Brain Hates Your Cubicle—Here’s How to Thrive Anyway (Psychology Today)

Arvind Jain: The Humble Builder Behind Glean And The Future Of Agentic AI (Forbes)

The Outsider Advantage: How Naïveté Fuels Billion-Dollar Startups (Forbes)

Never Make a Bad Choice Again by Embracing Self-Nudging (Psychology Today)

The Psychology Of Better Choices: How Startups Are Rewiring Our Habits (Forbes)

Staying Curious Is the Most Dangerous Thing You Can Do (Psychology Today)

After Arkansas: The Future Of FEMA And U.S. Disaster Relief (Forbes)

Ryan Gellert on Building a Future Where Sustainability Is Not Optional (Forbes)

Why Struggling (the Right Way) Helps You Learn (Psychology Today)

Want to Make Better Decisions? Copy the Slime Mold (Psychology Today)

Your Brain Was Built to Forget—Make It Work For You (Psychology Today)

The Case For Terminal Optimism In An Unpredictable World (Forbes)

The AI Coordination Revolution You Haven’t Heard About Yet (Forbes)

Where and how to get involved

A book is coming.

The Curiosity Code (yes, the book) is officially in motion. I’ll be drafting chapters this fall, weaving together insights from CEO interviews, classroom sessions, and conversations like the one we’re having here. If you have stories about range, curiosity, or unorthodox paths — I’d love to hear them in the chat or comments.

A podcast is brewing

We’ve started taping episodes for the first season of The Curiosity Code podcast. Early guests include the CEOs of Lovesac, Grindr, NOVOS, Front, and Aampe. Can’t wait to launch this properly in a few months.

I am currently conducting a study on range and how it impacts people’s career trajectories. Ten questions and a name will get you on the hall of fame as we pump up the n on the study. Link below - thanks for considering it!

You’ve reached the end - thanks for scrolling all the way down.

Curiosity is best when enjoyed in great company.

Refer this issue and grab a chance to get a tester package of Neuro blessed by the founders themselves (randomly selected from all referrals made). I’m connecting with the duo for a longer chat, recorded for the upcoming Curiosity Code podcast, and will be grilling them on their curious path to setting up the company. If you want your question included in the mix, hit me up via the Substack chat or email.