What campuses should do in response to Charlie Kirk’s assassination, but won’t

We need more tents, and more bad debates

Tocqueville’s fault lines have grown up into real-life fractures now, and what he saw as America’s resilience has decayed into fragility and division

The American voter has grown too weak for the crown they wear, addicted to affirmation, stripped of agency, and too brittle to withstand opposing views

Polarization is only the base layer of the problems we face, ideological puritanism, commercialization of politics, and hollow leadership have hollowed civic life

Rebuilding starts with more tents, more debates, even bad ones as my student reminder me, to re-train the democratic muscles and restore curiosity.

We all have our moments of delusional grandeur.

A periodically recurring one of mine is imagining that I know what Alexis de Tocqueville must have felt as he wandered this country, an early draft of his 1835 Democracy in America in hand, jotting down observations about the nascent country’s fault lines and its future trajectory as it ascended to the throne of the Western world.

His writing was both foundational and flawed, containing a host of sweeping conclusions and monolithic caricatures based on anecdotal evidence, all of which was nestled within a framework that still cuts close to ground truths the United States is wrestling with now.

Some of his insights were outright prescient, including how he warned that only God could mend America’s racial divide: “and although the law may abolish slavery, God alone can obliterate the traces of its existence.”

Nearly two hundred years on, many of Tocqueville’s fault lines have come to look like fractures, and what’s worse, we’ve carved the landscape with entirely new ones he could never have foreseen. You see, if Tocqueville was impressed by anything, it was how American democracy was uniquely buoyant and resilient in comparison to the old continent.

Today, it feels more fragile than ever.

Many things have been written about Charlie Kirk’s assassination in the past few days. Tocqueville, I suspect, would have seen both the vile celebrations and the feverish calls for revenge as proof that the democracy he once saw as an unstoppable force was now collapsing under the gravity of its own divisions.

To call this moment one of ‘polarization’ is to mislabel the disease the country is suffering from. What we are witnessing are violent convulsions that arise from the decaying of the civic body itself.

And at the heart of the disease stands the American voter, who has never been more ill-equipped to bear the weight of the power their status confers.

The infantilization of the American voter

We need better terms and concepts for what has happened to the civic body of the United States.

Where de Tocqueville once saw a gleaming beacon of hope for all countries, we now find a smoldering mess where polarization doesn’t fully explain what’s happening. You can be polarized, divided into two camps, and still be civil about the engagement. Just look at how Japanese fans clean up after themselves at World Cup matches, even after a big win.

Polarization is merely the foundation of the witch’s brew that’s proving more poisonous by the moment. Add ideological puritanism, the commercialization of the political sphere, and a bipartisan disdain for learning from the past, and what we have left is an empty husk of civic life.

The voter is the granular unit of account here, and while no single individual one is to blame, collectively the voters are all at fault, as unfair as the accusation may seem.

And deeply unfair the current infantilized state of the American voter is. The system has worked tirelessly to strip them of real agency for decades. From Gilens onwards a generation of researchers have shown how the United States routinely fails to adhere to the will of its citizens. Katz and Mair aren’t exactly wrong when they argue that the political system works like a cartel, and it’s more clear by the day how the US political duopoly functions more like rival corporations than civic stewards, staging endless showdowns not to solve problems but to monetize disagreement as a reliable get-out-the-vote strategy.

Both sides know the value of keeping a good problem unsolved.

The result is a voter left disenfranchised in everything but form, able to cast a ballot, yet unable to change a thing. The returns to partisanship trump that of real civic engagement, and with no reason to flex the muscles that democracy was designed to strengthen, the voters themselves have withered, many of whom are now entirely unfit for its most basic work: speaking honestly together about where the country is headed.

The term Capturenomics comes closest to the concept I’ve observed in my most de Tocquevillian moments since moving to the United States. The American voter has been captured slowly, seduced by forces they welcome, like a vampire feeding on them under the sheets after night has fallen, draining them until they are reduced to a puppet of political consumption with no other task than to prop up the status quo.

The tragedy is not just that voters are divided. It’s that they have become weak to the point where many of them are too fragile to even hear a contrary view, let alone absorb it.

Too many voters are now so addicted to affirmation that their egos are unable to survive the sting of being wrong. Somewhere Fukuyama’s “end of history” disciples are sweating, because clearly democracy, particularly the American kind, wasn’t it.

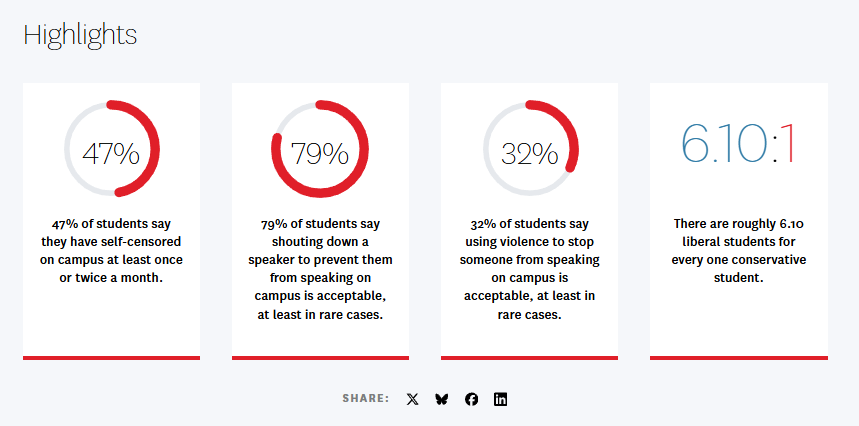

Not even at Harvard, where free thought is supposed to be at its strongest, do students pass the test. In its results this week FIRE reports that 32% are fine with violence to silence a voice.

When the words of others become dangerous, our thinking and confidence in it has become weak.

That’s the crack we now have to mend if we’re serious about saving democracy. We need to rebuild the voter.

Rebuilding the voter: more tents, more voices

In their desire for ideological conformity, the American voter has become entirely uncurious. The average voter is equally uncurious about why the other side believes what it does as they are about the evidence behind their own slogans and party-led orthodoxies.

And a democracy without curious voters is already on life support. You see, there’s nothing simple or straightforward about building a prosperous society. The blueprints for a healthy nation will never fit neatly onto a placard waved at a rally, and clickbait headlines will never transmit the depth of thought and effort required to create a better future through the political system.

The fundamental problem at hand is that voters now experience politics more like a fandom or a spectator sport with zero tolerance for discomfort. But governing is not a highlight reel of ours dunking on theirs. It is necessary, and often painful, compromise that requires patience and constant exposure to people who do not agree with you.

If democracy is to survive, the average citizen needs to re-discover the muscle memory of a good argument, not just one where our side won. We need to celebrate the willingness to sit with an idea you hate and we need to recognize that sometimes our being proven wrong can be more valuable to society than being right, because the marginal value of being proven wrong is infinitely greater than the hollow pleasure of being validated again.

Many have rightfully noted how Charlie Kirk himself was no master of reasoned discourse. His debates were often a spectacle in their own right, and the playing field was tilted to the advantage the crew that edited his social media clips.

And while I object to many, if not most, of the ‘truths’ he found self-evident, in his process I find something truly worth respecting. He consistently showed up for the debate. He entered hostile rooms and brought his arguments straight into the lion’s den without apology.

A student left me thinking this week when they suggested that a society willing to allow bad debates may be even more important than one that only permits good ones.

The process matters more than the quality of the performance. Our youth especially need to see the process in action, and they need to see flawed debates, even bad ones, because from there we can begin rebuilding the muscles of democracy and finally have good ones.

The immediate instinct after an attack as gruesome as this will be to shut things down and to narrow the space of conversation in the name of safety or sensitivity. Or perhaps more cynically, simply to avoid legal liability.

That is precisely the wrong lesson to teach our youth that is watching us keenly. Now more than ever, we need more tents on more campuses. We need more arguments and more uncomfortable exchanges. We even need the bad ones. Especially the bad ones.

Democracy doesn’t die from too much disagreement, it dies from when it no longer has enough of it. It withers when citizens no longer know how to argue and when they become too weak to withstand discomfort.

I am not asking anyone to honor Kirk’s legacy or his political views, but I invite all of us to embrace the most admirable parts of Kirk’s process, and to pick up where he left off.

Bring your thoughts into the tent and set them up right in the public square, in the messy, difficult, often ridiculous work of disagreement. Because I fear that the Universities themselves wont do anything of the sort.

That is how you rebuild the voter and how you inoculate democracy against the impending decay.

A book to read

Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville

Tocqueville dissected America and in doing so, highlighted virtues as well as its blind spots and contradictions. Nearly two centuries later, his blend of admiration and unease feels eerily current. Read this one not as gospel, but as a mirror held up to both then and now.

A thing to do

Build your own debate muscle

Research shows that debating is actually one of the few things that can literally make people more cognitively nimble. Push yourself into disagreements and learn to enjoy the sting of being proven wrong. It’s one of the most reliable ways to strengthen the intellectual reflexes democracy depends on.

A thought to have

Civic duties and civic virtues

Voting is the bare minimum, and we barely get even that done. The richer questions we should be tackling with are what does it mean to live as a citizen, not just a consumer of politics? Virtues like curiosity, resilience, and tolerance for discomfort are the scaffolding of democracy. Without them, ballots are empty gestures.

A product to

hateloveThe Finnish Army tent

The one with the ingenuous design feature: when it rains outside, it also rains inside. It’s more initiation ritual than survival gear, and at best its a leaky shelter that forges resilience in the cold. Cheers to all W05 cohort colleagues who half-lost a limb to frostbite under its canvas walls, and here’s to all the wonderful late-night debates we once had in them.

Recent writings on Forbes and beyond

Latest: 3 Habits That Set Superperformers Apart From Others (Psychology Today)

Only Fools Use “ChatGPT Wrapper” As A Slur Today, Here’s Why (Forbes)

5 Ways We Make Ourselves Less Intelligent Each Day

(Psychology Today)Born Smart or Built Smart? The Truth About Intelligence and Effort (Psychology Today)

We Have Six Months Until AI Breaks Reality, This Tool May Buy Us Time (Forbes)

Branding Is Leadership: What Modern CEOs Must Understand About Global Brands (Forbes)

Luxury Real Estate Isn’t Slowing Down, It’s Scaling Up (Forbes)

Why Your Neighbor’s New Car Feels Like a Personal Attack (Psychology Today)

Why This AI Entrepreneur Paid Six Figures For A Lunch With Benioff (Forbes)

The Power of "No": How Rejection Builds a Life Worth Having (Psychology Today)

What’s Holding Back Sustainable Business? The Challenges That Matter Most (Forbes)

What’s Next For Beverages In 2025? CEOs Predict The Path Forward (Forbes)

Why This Nasdaq Listed CEO Changed His Mind About AI, And What It Took (Forbes)

In Defense of Intuition: Why Gut Feelings Deserve Respect (Psychology Today)

Your Brain Hates Your Cubicle—Here’s How to Thrive Anyway (Psychology Today)

Arvind Jain: The Humble Builder Behind Glean And The Future Of Agentic AI (Forbes)

The Outsider Advantage: How Naïveté Fuels Billion-Dollar Startups (Forbes)

Never Make a Bad Choice Again by Embracing Self-Nudging (Psychology Today)

The Psychology Of Better Choices: How Startups Are Rewiring Our Habits (Forbes)

Staying Curious Is the Most Dangerous Thing You Can Do (Psychology Today)

Ryan Gellert on Building a Future Where Sustainability Is Not Optional (Forbes)

Why Struggling (the Right Way) Helps You Learn (Psychology Today)

Want to Make Better Decisions? Copy the Slime Mold (Psychology Today)

Your Brain Was Built to Forget—Make It Work For You (Psychology Today)

Where and how to get involved this August

AI for MBAs is official in review now. I’m looking for bold research subjects who are willing to read a chapter, like The MBA’s History of AI and the AI Family Tree, or the Ironclad Business Model. 6000-8000 words for you, a few comments and thoughts for me. Email to get involved!

Study #1: Seeing if Kvashchev’s experiment holds water.

We’re enrolling up to 200 participants for a lighthearted study on whether creative problem solving actually does a thing to our cognitive performance. Join here!

Study #2: Range as a predictor of leadership success

I am currently conducting a study on range and how it impacts people’s career trajectories. Ten questions and a name will get you on the hall of fame as we pump up the n on the study. Link below - thanks for considering it!

You’ve reached the end - thanks for scrolling all the way down.

Curiosity is best when enjoyed in great company.